Table of contents

Open Table of contents

Introduction

Phishing is still one of the most commonly observed initial access vectors in cybersecurity intrusions. Sadly, the phishing investigations of today are, on average, significantly more nuanced than those of the past. In the old days, you could simply glance at pass/fail for SPF, DKIM, DMARC, notice that the subject line of the email was related to Russian Brides, and quickly conclude that an email was, at least, not good.

To be clear, those emails haven’t vanished. But, due to the rise in popularity and quality of secure email gateway product offerings, if you work at any medium+ sized organization, you’re probably seeing a lot less of them.

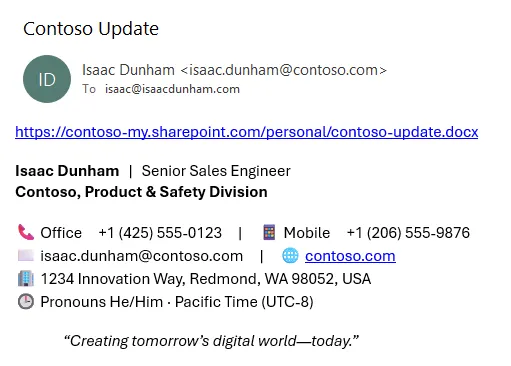

Today, a phishing email (that isn’t automatically handled by email security products) looks more like this:

Properties of this email:

- Links to a legitimate business domain (

contoso-my.sharepoint.comis the SharePoint & OneDrive subdomain for Contoso) - Passes all validity checks - SPF, DKIM, DMARC

- Includes legitimate (though fake in this example) contact information

- No language expressing extreme urgency (“act now”, “within 10 minutes”)

- No coercive language (e.g., threats, penalties)

- No request for credentials, MFA codes, wire transfers, or other sensitive actions.

- Clean, consistent branding with no odd formatting, spelling, or grammar errors.

- Professional subject (“Contoso Update”) with a neutral tone.

- No attachments — just a hyperlink.

- Message is addressed directly to the recipient’s email, not a mass/anonymous mailing list.

- Running the URL through any URL risk scanner returns a clean result.

All traditional data points indicate that this email is legitimate and benign. And yet, it’s not. It is, as I have observed it hundreds of times, a phishing email that either links to a fake login page that steals credentials or to a compromised site hosting malware. The way adversaries accomplish this feat is as follows:

- Compromise a legitimate business account through conventional phishing, password spray, stealer malware, etc.

- Upload a malicious document to the account’s personal OneDrive

- Use the “share” feature to provide access to a set of recipients based on who the user has recently interacted with via email

- Send emails to these recipients with a link to the malicious document.

- Reference previously sent emails to provide a legitimate-looking email signature.

- Use an extremely vague and sparse email body and subject. For example, “

<Company Name>Update”.

Once the user receives it, all they see is a legitimate-looking email including legitimate-looking content. If they report the email as related to phishing, most often, their Security Operations Center (SOC) function will simply mark the email as low risk or not a phish. This isn’t typically done out of incompetence or negligence, but an inability to perform due diligence. The URL is a OneDrive link that was shared with a specific recipient. A SOC analyst leveraging their own account simply doesn’t have authorization to access the document; only the recipient does.

From my experience, this is the most successful phishing email of the modern age.

The Modern Phish is more sophisticated than its ancestors

What Are We Doing Wrong?

With The Modern Phish, we are clinging to old ideas. We expect a phish to look like a Nigerian prince scam. We expect a phish to come from rnicrosoft[.]com instead of microsoft.com. We expect the phish to tell the user that if they don’t click a link immediately, they will be fired.

But that’s not what the most successful phishes look like today. They’ve not looked like that for that years. The fact of the matter is, if you have a remotely decent email security gateway, 99% of the low-hanging fruit of what you expect a phish to look like has already been stopped long before reaching a user. What remains is the modern phish. A hard-to-discern phish. A phish that will even fool a user who has gone through every phishing training module. It is a phish that presents no outwardly suspicious URLs, does not fail SPF/DKIM/DMARC, has no shady attachments, is not from a (relatively) strange sender, and features nothing profoundly strange in the email subject or body.

How do we Detect This?

Anomaly Identification

The only surefire way to detect The Modern Phish is to revisit an old idea: anomaly detection. We must identify the odd communique. We must intercept the strange update letter. We must stop the weird invoice. And, unfortunately, we must suffer for it.

Anomaly detection is hard. I think we knew that at least as early as 1987 from Dorothy Denning in An Intrusion Detection Model. Almost inherent to any attempt at anomaly detection is noise generation. Is the third-party legal consultant sending you a Docusign link after 6 months of no interaction a sign of a compromised account? Or is it just a normal interaction? You can’t be sure until you look.

Signature Identification

There are patterns to suspicious emails. We can all probably come up with a long list of frequently suspect subject key words and phrases. Some examples include “remittance,” “invoice,” “missed call,” and “shipment.” Unfortunately, there’s a reason these are common phishing lures: they are simply common. You might be shocked at how much legitimate email uses a word like “remittance” in the subject line.

Still, I have identified what seems to be a moderately higher fidelity means of identifying The Modern Phish. They usually include most/all of the following properties:

- Come from a sender that has not emailed the particular recipient in a long time (3+ months)

- Include generic subject lines

- Of particular note are subject lines mentioning the company name of the sender.

- Of extreme note are those that mention the company name with a typo. E.g., instead of a subject line mentioning “Acme Corporation” from a sender at AcmeCorporation[.]com, a subject line mentioning “Acmecorporation”.

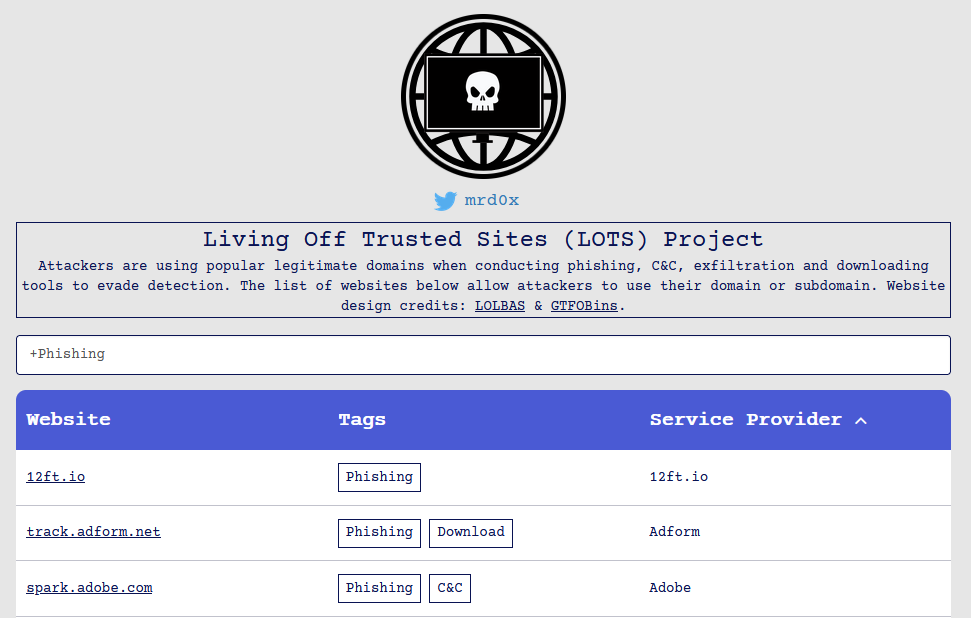

- Features a URL to a domain commonly abused for phishing.

- You can find a fairly comprehensive list by filtering for “Phishing” from the LOTS (Living Off Trusted Sites) Project: https://lots-project.com/

- In particular, I find domains related to Dropbox, Docusign, and

*-my.sharepoint.comto be the most concerning.

The LOTS Project is an excellent resource for identifying abused domains

Detecting the Successful Phish

Finding a successful compromise from The Modern Phish is a bit easier than finding the phish itself. You will need to leverage 3 evidence sources:

- Authentication logs

- Network connection logs (web proxy logs are most preferable)

- Email application logs featuring sent URLs / domains

With these, you can identify (1) anomalous authentications that occur shortly after (2) a connection to a known abused domain, and (3) what email may be responsible for the user getting phished.

Pseudo KQL-esque detection logic might look like this:

AnomalousAuthentications

| where TimeGenerated >= ago(30m)

| extend AuthTimestamp = TimeGenerated

| join (

NetworkTelemetry

| where TimeGenerated >= ago(30m)

| extend NetconnTimestamp = TimeGenerated

) on UserName

| join (

EmailTelemetry

| where TimeGenerated >= ago(14d) // further lookback than auth/netconn telemetry, as emails may be old

| extend EmailTimestamp = TimeGenerated

| where EmailUrl has_any (LOTSDomains)

) on UserName

| where AuthTimestamp >= NetconnTimestamp and NetconnTimestamp >= EmailTimestamp

| project

// Your auth telemetry properties

AuthTimestamp, IpAddress, Location, RiskDetails,

// Your netconn telemetry properties

NetconnTimestamp, DeviceName, RemoteUrl, InitiatingProcessFileName, InitiatingProcessCommandLine,

// Your email telemetry properties

SenderFromAddress, Subject, RecipientEmailAddress, EmailUrlWe Found a Weird Email. What do we do with it?

I have spent more time than I’m happy with frustratedly looking at “weird” emails. Ideally, you’d be able to just use a feature like Exchange’s “Impersonation” to act on behalf of the recipient to view any documents shared with that recipient. Unfortunately, this does not work. Instead, you have some less-than-perfect options:

- Reach out to the end user and warn them about the email.

- This is bad because it makes your users think you’re reading all their emails, is time-consuming, and does not scale with a large user base.

- Delete the email.

- This could be bad, because there’s a non-zero chance that the email is legitimate. And, if it is in fact something like a legitimate invoice email, that’s likely something you don’t want your end user to miss.

- Do nothing. After all, there’s a billion other things to do, and there is no evidence of an active threat with the information available to you.

- This is probably what most organizations end up doing most of the time. But doing this sucks, doesn’t it?

In this situation, I lean towards a variation of option 1. You should send an automated notification from a security department email address that is absolutely not curated for the particular end user or email in question. It should provide some useful context to not scare users, including:

- A notice that the email may be illegitimate

- A recommendation for the user to reach out to the sender through an out-of-band mechanism (not via the same email address as the sender address) and confirm the validity of the email

- Some carefully worded verbiage to let users know that this very particular email was flagged as suspicious by an automated system (e.g., your detection ruleset), and was not flagged by a human that does nothing but sift through everyone’s email all day

A User Reported a Weird Email as Phishing. What do we tell them?

A trap that I see many organizations fall into, despite their best efforts, that results in user account compromise is a policy of determining that reported emails should either be classified as benign or phishing. With the rise of The Modern Phish, this is simply not an effective paradigm. The Modern Phish (a strange, legitimate-looking email including a URL of undeterminable reputation) is like an envelope sealed with a biometric lock. Whether or not its contents are legitimate cannot be determined until opened by the recipient. If your organization follows a benign vs. not policy of email classification, your analysts will likely close out a phishing report of The Modern Phish as benign, leading to an end-user notification that the email was benign, and then the user, believing the analyst has performed a deep dive (that they are simply incapable of) into the legitimacy of the email, may ignore their gut instincts, click into the email, click into a strange document, and, probably, get phished.

I recommend a new, novel classification of email: unknown. It’s really that easy. You can use canned response verbiage like the following:

User,

Thank you for your suspected phishing email report. We appreciate your vigilance.

Unfortunately, the legitimacy of the email from

<SENDER>with subject lineSUBJECTcould not be identified as benign or phishing. This is because the contents of the email include a link to a file shared with you hosted on a third-party tenant’s service. This file was shared with your specific account, and our analysts are unable to view it on your behalf.It is common for adversaries to compromise legitimate business email accounts and then use them to host and share phishing documents with specific recipients from their contact list. Thus, while you may recognize the sender, you should exercise caution in interacting with this email.

In case the email sender’s account is compromised, we recommend reaching out to the sender through a method other than email to confirm if the email is legitimate.

Regards,

Security Team